Why I Write About the Things I Do.

I grew up in Minnesota, in a German home. My parents were immigrants; both had lived through the war in Germany. Often, they talked about what they had experienced during those horrific years and even told stories that were not widely known—the terror of hiding in a bomb shelter during the nightly raids on Berlin, the desperate post-war famine in Germany, barely surviving the brutal Gulags of Russia.

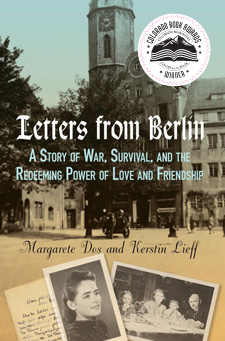

In 2013 I published my first book, Letters from Berlin, the story of my mother’s life growing up under the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler. It was so well-received (Amazon gives it a 4.5-star rating with over 300 reviews), it won the Colorado Book Awards for “Best of Biography.” I decided then and there to write more about what I call “the second stories of Germany,” those stories we seldom hear because they come from the wrong side of history.

I went back and replayed the hundreds of tapes my mother had left me with her stories of life in Germany during the Second World War. On several occasions she told me about die Flucht aus Ostpreußen—the escape out of East Prussia—or die Flüchtlinge—the refugees—and during most of those interviews, she wept when she spoke. She told of the time when trainloads of East Prussian refugees—most of them women with children—flooded into Berlin, frightened and disoriented, telling stories that would make you shudder. A girl missing her ring finger for having run so fast when the Russians arrived, her ring caught on a nail, so frightened, she tore it right off. The many stories of plunder and destruction, rape and senseless murders.

Something about East Prussia began to nag me. I wanted to know more and perhaps write about it. After all, East Prussia no longer exists. Then there was the idea d to write about children, who, like my half-brother (See “A Boy Named Klaus”), became orphaned during the war.

It was a random thing that I learned about the Wolf Children. I was searching the Internet wanting to find stories like the one about Klaus, and in my search, Google kept sending me to German websites that mentioned the lost children of East Prussia. Bingo! Here was a story about a land that no longer exists with children who no longer had parents. This was the story I wanted to write! I Googled on and was astonished to find that almost nothing about them had been written in English. How could this be? I thought. 20,000 children, suddenly left to fend for themselves, the roughly 5,000 of whom survived, never given an audience for their stories?

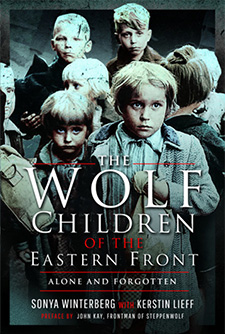

I had no idea where to begin writing about die Wolfskinder (the Wolf Children), but in hindsight, the answer was staring me in the face. Of all the German books I found, there was only one that spoke simply, a book written in understandable language, in the voice of those very children. It was the book written by Sonya Winterberg with its haunting photographs by Claudia Heinermann, Wir sind die Wolfskinder—Verlassen in Ostpreußen, “We are the Wolf Children—Forsaken in East Prussia.”

I was so moved by the stories, and so convinced that they needed a broader audience, that I reached out to Sonya and offered to help adapt her book for an English-speaking audience. Sonya had spent years tracking down the few surviving Wolf Children with the intent of interviewing every one of them. At the time only about eighty were still alive. Sonya didn’t stop at merely researching or relying on phone interviews. She attempted to visit every Wolf Child she could and nearly every one of them in their own homes, where the comfort of familiar surroundings often produced unpredicted moments in which memories long buried sprang to mind. Sonya most graciously agreed, and three years later, we now have this most beautiful English version about the orphaned children of East Prussia: The Wolf Children of the Eastern Front, Alone and Forgotten.

Imagine: Children, alone in the woods. Children fighting off the Russian army, alone. Children abandoned. These are The Wolf Children of the Eastern Front.

Follow Me